An atheist friend once caught me off-guard when she declared, “There’s a reason for everything.” It turns out she meant there is a rational, scientific explanation for everything that exists or happens, not that there is a Divine Purpose behind events. Her faith is in scientific progress to bring safety and stability to her life and to reveal life’s mysteries, given enough time. Despite this apparent secular worldview, she calls herself spiritual.

As for so many, her spirituality focuses on personal growth and her desire to be in sync with natural forces governing the known world and holding it together. This spirituality also favors ethical, psychological, and political interests more than metaphysical ones. There is no necessary belief in the existence of a spirit realm or souls that live on after the body dies, much less faith in a religious concept of God.

This disenchantment with traditional ideas of God and long-established creeds has led to popular use of the phrase spiritual but not religious (SBNR). The implication is that individualized beliefs are more consciously arrived at and are more sophisticated and equipped to handle the complexities of modern life. World religions based on the embrace of objective truth are assumed obsolete – too rigid and narrow to serve the needs of individuals in the Information Age. Acclaimed film director Martin Scorsese lamented the difficulty getting top actors interested in his religious-themed movie Silence, saying, “Several actors didn’t want to get involved with anything that smacks of religion in any way.” It’s curious that those calling themselves religious are usually comfortable calling themselves spiritual, but the point of SBNR is to maintain a clear distinction from religion.

The phrase spiritual but not religious was popularized by Bill Wilson, one of the founders of Alcoholics Anonymous. He believed the desire for intoxication was primarily a spiritual impulse and that alcoholics were unconsciously trying to “grope their way to God” as they sought reliable fulfillment in alcohol. In Bill Wilson’s view, religious belief requires a higher order of maturity and complexity than does mere spirituality. But even as he greatly respected religion, Wilson made clear that Alcoholics Anonymous did not require religiosity for recovery from addiction. His use of SBNR was a practical and wise acknowledgement of legitimate emotional wounds some alcoholics suffered in their religious upbringing. A large number of alcoholics also had an aversion to anything churchy, stemming from religions’ typically moralistic approach to alcoholism. For him SBNR was a frank statement of humility, the need for rudimentary spiritual assistance, and was not necessarily a declaration of permanent independence from religion. Wilson insisted, “…good theology ought to ask every man’s question: Do I live in a rational universe under a just and loving God, or do I not?” His AA sought to provide emotional room for alcoholics to get physically well while still wrestling with that question.

Wilson and his co-founder Bob Smith chose the term higher power, not highest power or God, to assist alcoholics in their efforts. Wilson and Smith might have found it ironic and maybe disheartening to see the modern practice of the SBNR idea move away from religious thought, rather than towards it.

So then many calling themselves SBNR do believe in a non-material realm and even cite experiential “touches” of the transcendent without specific mention of God. This person finds in a spiritual practice a bridge to the mysterious, and a way to gain agency over fearful and potentially threatening things in the experience of living. Love is often identified as the ultimate spiritual value, having mystical and protective properties within itself without a necessary connection to deity. God is love evolves into Love is God, with fear being the primary antagonist to spiritual growth. Oprah Winfrey espouses this approach in her faith declaration, “I believe every single event in life happens [as] an opportunity to choose love over fear.” The objective is a therapeutic one, based on a personal growth model of spirituality rather than on obedience to the will and purposes of one God, or gods, or a higher power. The road map to love means first loving the self: one must listen to oneself and follow one’s own dreams.

This approach may even lead to organized groups and communal rituals, but without a defined object of worship that is higher than the self, the desire for self-fulfillment becomes the foremost concern and the primary power with which to contend. One’s intentions are imbued with a quasi-omnipotence, attaining divinity status. If one’s intentions are faithfully released to the larger Universe, then the divine in oneself aligns with the divine in the Universe to bring the intentions to fulfillment, goes the belief.

American political discourse increasingly appropriates this self-help language to stigmatize opposing views as necessarily fear-based. Political opinions and actions are less frequently assessed in a moral context as right and wrong, or even in a utilitarian way as better or worse, but instead as choices between one view or a fear of that view. A SBNR might dismiss an opposing point-of-view as a symptom of mental instability or as an irrational fear: something-phobic.

Despite the potential inaccuracy of that linguistic ploy, it may well be that the reaction against fear, or more specifically anxiety, is common ground for both the self-described SBNR and the religious person. Every human being has a keen desire to be free from internal anxiety. This is not a new concept emerging from the uncertainties of modern life. How to understand anxiety within the human condition reflects ancient questions and conundrums between philosophy and theology. Do we reason our way to transcendence or are we awakened to it, as something revealed? Is spirituality uncovered or birthed? Are human beings like onions whose crusty, brittle exterior just needs to be peeled off to reach the pure center? Or are we tainted throughout and in need of transformation? Every side to these questions have had their true believers for thousands of years.

How then does the modern seeker find clarity with such long-standing questions that have challenged the greatest minds of all time? I’m exceedingly reluctant to say what others should do, but here is an account of a spiritual experience that gave me some clarity I desperately needed, illuminated beyond intellect.

At age 21 I decided to give college life another try. My previous attempt was interesting but directionless, so I quit and went to work. After several low-paying jobs serving affluent people, I was resentful. So I resolved I’d never be among those who bowed to the rich. Back at a different university, I was hungry for knowledge and ambitious to learn something useful.

Despite my optimism I was very nervous about my future. But living with chronic anxiety was so normal for me that I wasn’t aware life could be conducted any other way. At the time I described myself as spiritual but not religious, though I understood very little of what I meant by that. In the midst of my confusion I had the first truly spiritual experience I am aware of, which happened shortly after my arrival on campus.

It was a Saturday afternoon and I was lounging around my dorm room when there was a loud knock on the door, a guy from down the hall. “Hey JJ, you wanna make twenty-five bucks for two hours work?” You better believe I did. This was 1979 when minimum wage was three dollars an hour, so this was good money. Off I went with him. “What are we going to do?” I asked. “Sell t-shirts,” he said.

A famous rock band was playing at the big arena on campus and there were already long lines of people outside waiting to get in. I was introduced to the boss man and he explained the deal: we were to sell bootleg t-shirts outside the arena. The official and legal merchandise happened inside the arena and were totally controlled by the band. We were illegal so keep your head down, he said, and if you see the campus police, keep moving. T-shirts were $5.00 each and I was given a box of them filled to the brim.

The boss let us in on an innovative sales technique: since we would run out of XL sized t-shirts first, we could still sell a t-shirt to someone requesting XL by reaching into the box with both hands, one hand holding a shirt and the other holding the tag that had the size labeled on it. Then, he instructed us, quickly pull out the t-shirt with one hand, thus ripping off the tag in the process. This way the buyer couldn’t see they were getting a medium or large-sized t-shirt instead of the XL they requested.

You might think cheating the customer this way would arouse pangs of conscience. But at that time, despite my claim to a personal spirituality, I placed greater value on personal shrewdness. I was determined to never play the fool for anyone. I found satisfaction in ripping off institutions and groups of people, especially if I considered the groups to be wealthy. It was vanity and avarice that really governed my thinking, but I easily deluded myself into believing I was striking a blow for the common man. I was a big fan of Steal This Book by Abbie Hoffman the Yippie leader who advocated small acts of subversive criminality to undermine the established order.

On the surface I affected a confident pose about myself, but deep inside I felt the confusion of my sloppy value system. In a conversation with a “religious” guy a week before I had asked, quite sincerely, “How do you know the difference between right and wrong?” He said, “When I’m considering the morality of an action, I ask myself two questions: Does this please God, and does this glorify God?” I had no idea what he meant by glorify God. It sounded like the kind of high-handed religious talk I was moving away from. Pleasing God seemed simple enough though, in theory. Just do good deeds.

Back at the arena I began walking around with my box of t-shirts. They sold quickly, with people gathering around thrusting five dollar bills at me. In twenty minutes I had sold several dozen and I had a fistful of cash to show for it. I was feeling flush with success, but then I reached the point where someone asked for an XL t-shirt and I had no more of them. As instructed, I accomplished the maneuver of slyly removing the tag, thus cheating the customer.

As I mentioned, this normally wouldn’t have bothered me much. I would have fairly easily convinced myself that the larger objective of getting over on a big corporation, even a rock and roll one, justified this small indiscretion against the customer. But for some reason those arguments weren’t available to me this time. My stomach felt queasy.

I stepped aside to sort out my thoughts. The two questions I’d heard the week earlier came unbidden to my mind: Was this pleasing to God? Was this glorifying to God? My stomach still hurt.

No, I decided, what I was doing was neither pleasing to God nor glorifying to God – how could it be? I immediately found the boss and gave him all the money and remaining t-shirts and told him I quit and didn’t want any payment. “What’s wrong?” he asked, holding the wad of cash. I surprised myself by saying, “It’s not honest,” the words coming out all by themselves. He smirked and said, “You’ll learn someday.”

As I walked back to the dorm a startling euphoria settled on me. At the same time I felt lifted up, like I was walking on air, relieved and happy. Back in my room I put on a record, a Beethoven symphony. The music rose and I could almost see it filling the tiny room and swirling about. I was possessed by a beautiful sweetness, completely free from anxiety, at least for now. This moment was clear, utterly sober and superior to any experience I had before. Something far more expansive than myself was present and drawing me closer.

I mark that day as my first conscious contact with a spiritual – – something. Or was it religious? This much I understood: it was something new I lacked within myself by nature, something far grander than I could then fathom, and something that changed the way I felt about living. It was exciting, like finding a treasure or falling in love. I wanted to pursue it.

I pondered my religious friend’s advice. Pleasing God was about choosing right over wrong, I reasoned. But my understanding of right over wrong was incomplete, I intuited, until I could understand the second question. What was it to glorify God?

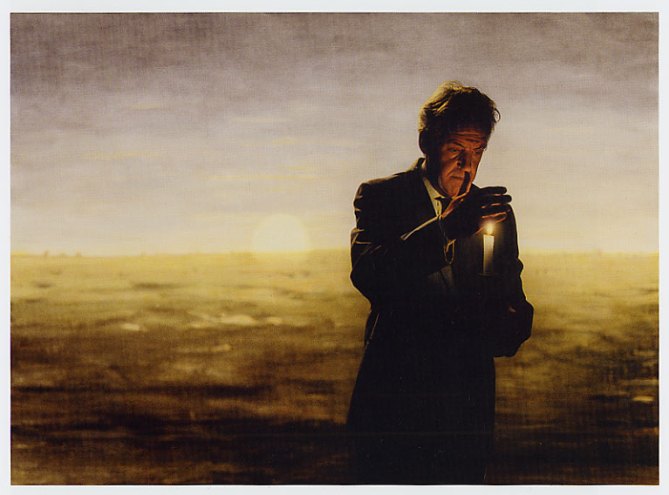

The following Summer some help came my way. I was leisurely strolling in downtown Manhattan on a beautiful sunny day, feeling great. A man sidled up next to me, matching my pace. It was a workman carrying a large package on his shoulder.

“How’s your faith?” he asked.

A little surprised, I said, “Uh, good I guess.” He had the word Shekinah emblazoned on his t-shirt.

“What’s Shekinah?”

He said, “God’s glory.”

“Really?” There it was again. “But what is it?”

“Shekinah is the manifestation of God’s presence on Earth. With you, maybe. See ya.” He turned sharply into a building and was gone. A shiver of recognition passed through me, thinking of my uplifting experience of months before. Could that euphoria be a Shekinah? What an interesting thought this was. I no longer cared if this new glow I had was called spiritual or religious or even weird – it was just too splendid to worry about that.

This guy used the word presence – yes, it was that. A veil I didn’t know existed was lifted, certainly not by my powers of reason or imagination. A highly personal presence that was not mine had beckoned me in. It was glorious, and sublime. If this was God’s glory on Earth I was more than willing to call it Shekinah and follow where it led me.

Whatever Shekinah was, it banished my anxiety. I wondered what more I could do to glorify God. Maybe all I needed to do was stay out of the way and Shekinah would come to me as before.

In the end I settled on calling this a spiritual experience. It changed me and set me on the spiritual path I’m on to this day. A path that draws me along – I take steps without knowing exactly where the path will lead. But as I take them my natural anxiety is muted and I am aware of a growing assurance that I am going to be okay.

In the late 1970s I lived in a rural university town where a significant number of people were thought of as hippies. They rejected prevailing bourgeois values and led back-to-the-land lifestyles. I respected their bold, independent ways and imagined myself a kindred spirit, even though I myself was thoroughly bourgeois.

In the late 1970s I lived in a rural university town where a significant number of people were thought of as hippies. They rejected prevailing bourgeois values and led back-to-the-land lifestyles. I respected their bold, independent ways and imagined myself a kindred spirit, even though I myself was thoroughly bourgeois.